So far I have made a grand total of seven and a half corsets. Two for me, four for friends, and one which is still under construction. The first one I made from a commercial sewing pattern, and it was such a ridiculous shape (even for a ridiculously-shaped garment like a corset) that I decided that drafting my own patterns was the best way forward. This plan was also borne out of two abdominal operations and an ongoing stomach-ache, which means that I don’t like to be squished too much around the middle.

Now I appreciate that seven and a half corsets doesn’t make my anything even faintly resembling an expert! But eleven years as a dressmaker, plus a year of fitting bridalwear, does give me some sort of clue as to the range of shapes and sizes in which the female form can manifest itself.

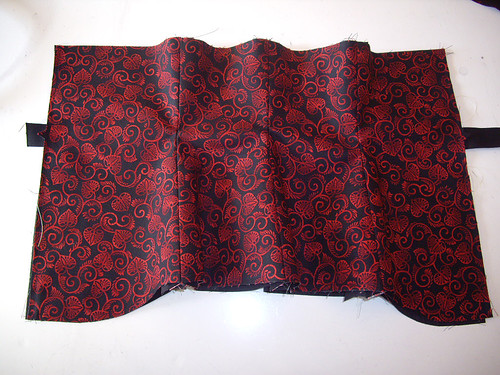

Here is a work-in-progress picture of the corset that I’m making at the moment:

You will notice that it has peaks and troughs, where it doesn’t lie flat on the table.

This is because (shock, horror) people aren’t flat.

I frequent a number of online communities for corset wearers and corset makers, and time after time I see pictures of completed corsets, often beautifully made, lying completely flat on a table.

Of course, the primary function of a corset is to reduce the size of the wearer’s waist. The best way to make this reduction very apparent is to do this by taking all of the reduction out of the side seams of the corset. This results in an extremely dramatic silhouette, and a very flat corset.

The trouble is, once again, people aren’t flat. They don’t squish only at the sides. My back, for example, has an exaggerated curve. If I were to wear a corset where the sides had been reduced but the back was straight, there’s no way it would be comfortable for me to wear. I also have a rounded stomach, so I need to make allowances for that in the shape of my corset, even if the intention is to make it appear as flat as possible.

My eight-panel underbust corsets are about the simplest style it’s possible to make whilst still taking into account the curves of the wearer. If I wanted to go for a much more precise fit, taking into account the shape of the wearer’s ribcage, or the curvature of their spine, I’d probably be looking at doubling the number of panels, in order to accommodate the complex curves.

(Complex curves is also the reason I don’t take orders for overbust corsets, by the way!)

Of course, the principle that people aren’t flat doesn’t apply only to corsets.

Kathleen at Fashion Incubator, for example, has two extremely interesting articles which explain why your trousers don’t fit.

And because most “industry standard” (as if there were any such thing) clothing is made to fit a B-cup, a great many of my customers are either women with larger breasts, or smaller women with curves they’re not “supposed” to have. Oh, and plus size women who don’t have shoulders like a weightlifter, which is what a great deal of clothing apparently expects from them.

When I become a Proper Fashion Designer (stop laughing at the back!), I can assure you that my clothes will be designed for, and modelled by, a whole range of different shapes and sizes of woman.

Believe me, this is going to be much, much more difficult than buying a set of slopers or a grading scale or some pre-set CAD software. If I use those, my clothes will come out the same shapes and sizes as the ones you see in the shops. And that rather defeats the object of making clothing from scratch in the first place.

Apparently I’ve never been one for doing things the easy way…

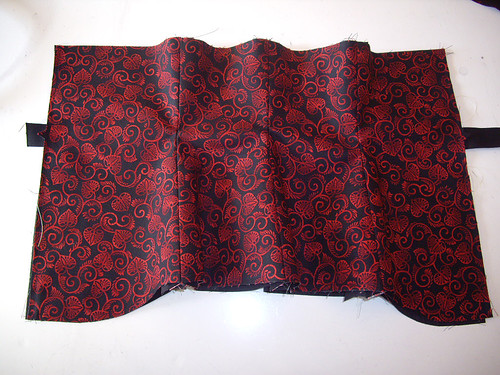

Like this:

Like Loading...