Way back in March (and doesn’t that seem like a lifetime ago?), I submitted an essay on Medieval Medicine and Astrology. The medieval period is a little earlier than I’m actually studying (I sat in on an undergraduate module, Because I Could), but I thought it would be a good idea to get a little bit of cultural background before diving straight into the early modern. I promised, at the time, that I would follow up the essay with a blog post or two about astrology and herbals, and then life intervened in the form of a global pandemic… and here we are.

I’ll admit that this isn’t the blog post that I’d intended to write (perhaps I’ll get to that later), but reading through so many different books in preparation for writing the essay, I became fascinated by how the authors’ views of astrology had changed over time. In An Illustrated History of the Herbals*, published in the 1970s, Frank Anderson is rather scathing about the inclusion of astrology in medical texts. He considers it ‘remarkable’ that Hildegard of Bingen, for example, writes a book so strongly rooted in twelfth century science, when ‘all of her other works are of a mystical and theological nature’. Anderson does concede that her writing represents the work she carried out in the convent, and that ‘Her Physica, in addition to displaying the state of knowledge then existing about the natural world, gives us a reliable picture of how medicine was practiced by the clergy.’ While Hildegard of Bingen’s prognostications are largely based on observable lunar events rather than the full complexities of astronomy, her work still represents a close relationship between medical and metaphysical thought.

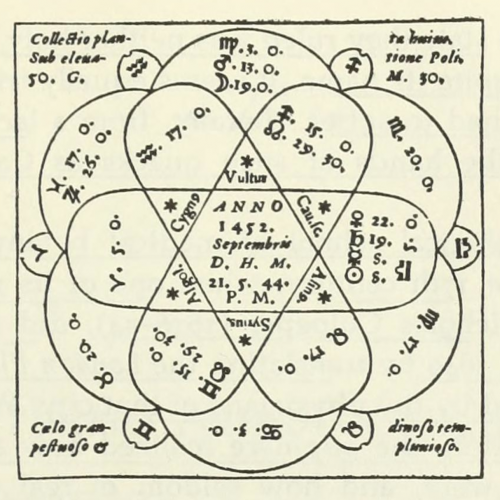

Anderson is similarly dismissive of the astrological diagrams found throughout Thurneisser’s 1578 Historia.** (I know, it’s not medieval, but, I couldn’t resist sneaking into the sixteenth century for a moment.) Anderson’s caption below this image of an astrological chart reads:

‘Scattered throughout Thurneisser’s Historia are numerous horoscopes with their arcane symbols. … Its major purpose was to baffle the uninitiated.’

But people with a medical training, who were the intended audience of Thurneisser’s book, would absolutely not have been ‘uninitiated’, nor would they have found the astrological symbols ‘arcane’. By the sixteenth century, astrological symbols were included in widely distributed texts, including almanacs and school books, so they wouldn’t have been particularly mysterious or secret during that time.

The emphasis of Thurneisser’s Historia was on using astrology to determine not only when to administer a particular medicine, but also when to collect the plants, and when to best prepare the remedies. This is a feature of many herbals right through to the seventeenth century. Anderson considers that the Historia’s ‘botanical value, as well as its medical value, was absolutely nil.’ Apparently, ‘the Historia delights the eye while offering little but offense to the mind’. I have to say that I find this assessment spectacularly unfair! While Anderson’s mind may have been offended in 1977, simply writing off astrology as valueless completely fails to take into account the educational background of the medical writers of the period, as well as prevailing cultural beliefs.

During the 1950s, Grattan and Singer*** were equally scathing about medieval medicine, describing the Middle Ages as a ‘thousand years of scientific degradation’, largely due to the teleological perception that few medical advances were made during this period. Singer in particular considered astrology firmly in the realms of magical, rather than scientific, thinking.

Consequently, it’s important to understand that this absolutely wasn’t the case from the twelfth century onwards. In order to become a physician and formally practice medicine, you needed a University education. For the “Trivium”, you learnt Grammar, Rhetoric, and Dialectic. These enabled you to study Latin, and to understand and discuss it critically and philosophically. Once you’d passed those subjects, you could go on to study the higher level “Quadrivium” – Mathematics, Geometry, Astronomy and Music.

The terms astronomy and astrology were sometimes used interchangeably, but whereas astronomy was a quantifiable, observable science, astrology could be considered its practical cousin – how you applied the astronomy you’d learned. In order to become a physician, your education came with both astronomy and astrology built in. Accepted by many as a basic scientific principle, the planets were considered to have demonstrable effects upon the body. This meant that an understanding of astrology was vitally important to the practical application of medicine, and definitely not unenlightened superstition.

*Frank J. Anderson, An illustrated history of the herbals (New York; Guildford: Columbia University Press, 1977) Astrological image from page 185.

A copy is viewable online from Archive.org.

**Leonard Thurneisser zum Thurn, Historia… (Berlin, 1578)

A copy is viewable online from Archive.org.

The illustration referenced by Anderson, shown above, is on page 57.

***J. H. G. Grattan and Charles Singer, Anglo-Saxon magic and medicine: illustrated specially from the semi-pagan text Lacnunga (London: Oxford University Press, 1952)