I’m continuing my experiments on YouTube with the first of what will hopefully turn into a series of PhD-related Vlogs – if I can get the technology working smoothly!

If you can’t be doing with videos, there is a transcription on YouTube of the closed captions, and I’ve also included an edited version below:

Hello! I’m Claire Smith, and welcome back to Eternal Magpie. This is going to be my first PhD “vlog”, if you want to call it that.

The first thing I want to say is just that I’m really, really tired.

I should have followed everybody’s advice and taken a break after finishing my MA dissertation, which was a very intense process, and before starting my PhD. For various reasons that didn’t happen, and I had a grand total of six days – all of which were filled with admin – in between finishing my dissertation and going back to campus and starting the whole process of the PhD. So far I’m two weeks in, and the hardest part has in fact been the admin! So many things to fill in, so many websites not working, so many hoops to jump through to make sure that all of my information is correct and everything is in the right place, and that I can be in the right place at the right time. (Which I’ve already failed at, by missing an online seminar that I’d been planning to attend. Good start there, Claire.) Fingers crossed though, I think I’m nearly sorted out now, which is a relief.

To keep myself organised, I treated myself to a beautiful leather handmade notebook cover from a company called HORD on Etsy. It’s hand-painted gold leather, it’s engraved with some of my favourite things (it’s got swords, which are always good), and on the inside they can engrave something personalised for you. I’ve got a diary cover, also by HORD, which has my name on it. This one I’ve had engraved with the beginning of the title of my PhD thesis. It’s based on a quote from Gerard’s Herball where he says that certain benefits of medicines performed by witches and alchemists are just “drowsie dreames and illusions”, and that you shouldn’t trust them. So I can keep that with me, it’s a removable cover, so when I fill up this notebook I can get a new one to pop inside, but I’ve always got the lovely cover with me. The stationery nerd in me is very, very pleased with that!

I’ve also had my first supervision meeting, and I think it went well!

Again, a lot of admin, and making sure that I know what I’m doing in terms of training and professional development, which is something that the university is really hot on providing. There’s a huge training program for postgraduates, so I’ve signed up to a few collections-based courses already, which happen throughout this term. Next term there’s a session on writing your literature review, which I’m definitely going to go to, because my first two important tasks are literature review-related.

The first one is to set myself up with an annotated bibliography, which I’m going to do in EndNote, because I got used to using that throughout my MA. It has its issues, like any piece of software, but most of the time it’s been really useful, not least for making the referencing process a whole lot quicker. Once you’ve got it set up right in EndNote you can just pop it into Word, and you’re done. Except when, right before your dissertation is due, it completely betrays you and refuses to format the references in the style that you’ve selected, which was extremely distressing, it’s really useful. You can put not only the details of the book into it, but there’s also a section for your own notes, so that’s going to be quite a good way of keeping everything in one place, staying organised, and also for having my own mini notes about each book. So, I’m going to set up my bibliography in EndNote; next term I’ll go and do the literature review training, and hopefully that will sort me out.

My other important task, which is the biggie, is basically to decide what I’m doing.

Frankly this is not something I’m good at, with any subject at all. I hate deciding what I’m doing. I like seeing where things take me, seeing where the research goes, following it down rabbit holes, and thinking, “oh I didn’t know that before, let’s compare this thing to that thing, and oh how does this impact on that?” I am not good at deciding right at the beginning what I’m doing.

That has to change now.

I’m thinking about two tracks for my thesis at the moment. They’re both about early modern witches, so that’s a start, but my first track is: am I going to follow the folklore and magical thinking and superstition and cultural beliefs that were prevalent during the early modern period, and place witches and medicine into that, or am I going to follow the history of medicine, and try and carve out a place for witches as legitimate medical practitioners in that sphere. That makes me slightly nervous, because the history of medicine is an increasingly well studied area, there are a lot of really top-notch experts, and it makes me feel slightly nervous as a brand new researcher, just finding my way, trying to make a place in that. The folklore and superstition part of things is really appealing to me just because it’s a fascinatingly huge subject, and going through the primary sources will be a really interesting way of seeing what people thought at the time, what people believed about witches, in material that has nothing to do with the witch trials. Obviously I’ll read up on the witch trials, but that’s not going to be my main focus of research.

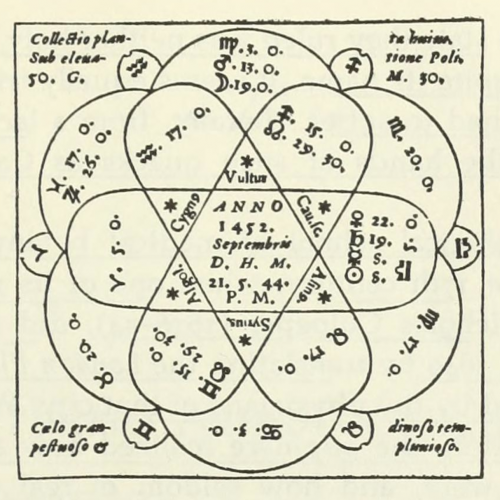

My main focus is going to be: what did people think about witches? What were their fears about witches? When a witch turns up in a book like a herbal, or an almanac, or a husbandry manual, what did people think witches were going to do? How did they feel the need to protect themselves against witches? Why did they feel the need to withhold information from witches? What did they expect the difference in outcome to be between, for example, a nice middle class, upper class, gentlewoman, somebody further up the social hierarchy, using a herbal recipe, versus what would happen if a witch read the same book, used the same ingredients, performed the same processes? How did they expect the witch to use that same information in a different way?

Again, I’m very aware that I don’t have all of the background knowledge. Most of my knowledge at the moment is directly from primary sources. It’s from reading primarily Gerard’s Herball, and a small group of husbandry manuals, so there’s a lot of secondary literature that I need to delve into. The first thing I’m doing about that is auditing a second year undergraduate module which is about “Belief and Unbelief” in the early modern period, looking at the processes and the structures of the church; looking at lay people and what they believed at the time; and also the importance of these beliefs to the the culture as a whole, and to the processes of state. We’re only two weeks in, and that’s already really, really interesting.

The other thing I’m doing is going back to basics by re-reading Sir Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic. It was published 50 years ago this year, so it’ll be a good starting point, and I can then add the following 50 years’ worth of scholarship on top of this foundation, and see where I’m at. What I really need to do is get stuck in – and also get stuck in to some primary sources, probably a couple that are available online. Certainly to begin with, it’s going to be much more convenient to start online, and really start thinking about what I actually want to do and which path I want to follow.

I’m very aware that I’m starting at the beginning, whichever direction I go in, and I’ve got a lot of reading to do, a lot of learning to do, and a lot of sources to look at. But I’m ready to get stuck in. I’m excited about it, a little bit overwhelmed, but I think that’s normal at the beginning of any big project.