I’m just heading into my third week of my MA History course, and the first two have already been full of fantastic connections.

First of all Tomos Jones, one of the PhD students at the Herbarium, shared this tweet with me. It’s part of the #folklorethursday hashtag, and the theme this week was the folklore of “elders”. The use of the word “crones” reminded me of a lecture I attended earlier this year by Dr Olivia Smith, who was talking about the origins of the phrase “Old Wives’ Tales” and some of the ways in which folk and oral traditions were marginalised by the cultural transition into print.

When I was taking notes during the lecture I wrote down, “how to separate actual women’s knowledge from reported Old Wives’ Tales???“, which turned out to be exactly the issue that Dr Smith was investigating in her research. When talking about Old Wives, or perhaps Crones (as above), these figures are often used as a shorthand means of describing an unreliable source or narrator.

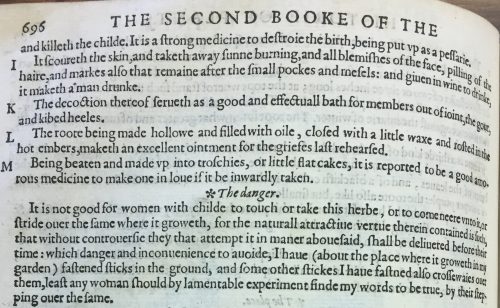

I went back to Gerard’s Herball to see what he had to say about Cyclamen as a love potion:

Being beaten and made up into trochises, or little flat cakes, it is reported to be a good amorous medicine to make one in love, if it be inwardly taken

Link to online copy of Gerard’s Herball, 1636 edition, page 845 (image shows 1597 edition, p. 695)

I particularly like “it is reported” as a nice vague way of absolving Gerard from any responsibility, should said love potion turn out not to work. Also, who reports it? Whose knowledge is being simultaneously reported and omitted by these noncommittal turns of phrase? That’s definitely something I’m going to be interested in when it comes to my dissertation. The majority of early printed herbals in English were translations and compilations from various earlier sources, but scattered amongst the empirical research is an awful lot of “it is reported” and “everybody knows”.

I think it’s also important to note that little round cyclamen cakes are not the benign floral love potion that we might imagine them to be. Gerard mentions several times, in both The Vertue and The Danger of the plant that it “killeth the childe” (see image & link above), to the point where Gerard advises that a pregnant woman should not even go near to the plant, nor step over it. While Gerard’s warnings may now seem a little overstated, we do know that Cyclamen is indeed toxic. In fact the Journal of the Cyclamen Society (Vol. 18, No. 1, June 1994, pp. 15-17) contains an article by Dr J. Rupreht regarding the dangers of Cyclamen purparescens as an abortifacient.

Folks, please, do not eat cyclamen, or attempt to recreate any of Gerard’s given remedies.

Last week we had a seminar to discuss how best to begin our dissertation research. One of the important pieces of advice was to read around our chosen subjects, and to look into other disciplines to find out different information and make connections.

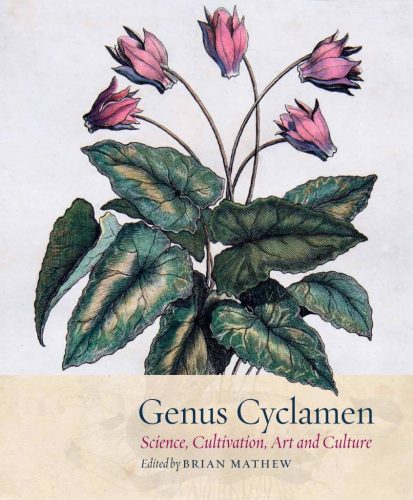

The following day I went into the Herbarium to continue my regular volunteering with the Cyclamen Society collection. While I was there, I flicked through a book which had been sitting on the bench next to my computer for weeks and weeks – Genus Cyclamen: Science, Cultivation, Art and Culture by Brian Mathew. Entirely by coincidence, I opened it at a page discussing the depiction and description of cyclamen in Gerard’s Herball.

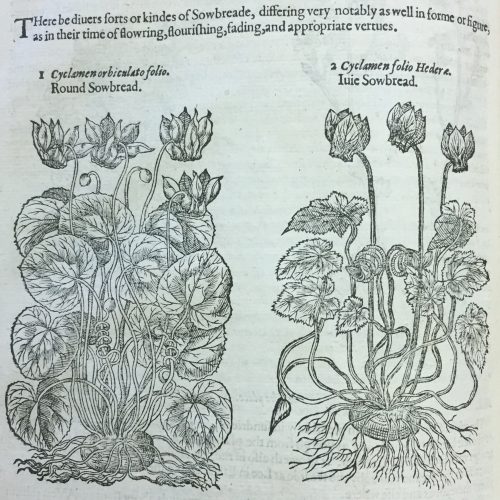

Gerard’s Herball of 1597 contains descriptions and illustrations of two distinct Cyclamen, C. purpurascens and C. hederifolium; C. repandum and C. balearicum were added by Johnson in 1636.

Genus Cyclamen: Science, Cultivation, Art and Culture by Brian Mathew (Royal Botanic Gardens, 2013) p. 450

There is also a fascinating discussion of the transition from manuscript to print in terms of the accuracy (or otherwise) of the illustrations that were used. Some had evidently been drawn from observation, and these allow for accurate modern identification. Others have been copied, often repeatedly, until the resulting illustration bears very little resemblance to the original plant. (Chapter 6.1, by Martyn Denney.) It was very common for printers to re-use woodcut blocks for different texts, so the same images appear repeatedly over quite a long period of time.

I’m looking forward to reading that chapter in full, and understanding more about the scientific difficulties that were inherent in the study of botany during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.